What if Atsu’s gravity-defying back draw—flipping a massive odachi into combat readiness—wasn’t just Hollywood flair, but a blade’s edge away from ancient reality?

Sparks fly as martial arts masters recreate her impossible spin, revealing a technique that’s equal parts genius and gamble. One wrong grip, and it’s game over… or is it? Unleash the truth: ⚔️🌀

Sucker Punch Productions’ Ghost of Yōtei, the PS5-exclusive sequel to Ghost of Tsushima that’s sold over 2.5 million copies since its October 2 launch, has gamers worldwide glued to their controllers, slicing through Ezo’s blizzards and volcanic ridges as the vengeful ronin Atsu. With its fluid combat drawing from real Japanese martial arts like Tenshinryū Hyōhō—a 17th-century school of swordsmanship, spear fighting, and more—the game blends historical authenticity with cinematic flair. But one move has ignited heated debates on X, Reddit, and martial arts forums: Atsu’s “back draw” of the odachi, a massive greatsword slung across her back. She unsheathes it with a flourish, tosses the blade skyward to catch it by the flat (not the edge), and seamlessly transitions into a two-handed grip for devastating swings. It’s visually stunning—equal parts ballet and brutality—but is it feasible in real life? Or just video game magic?

The short answer: It’s surprisingly doable, with a few real-world caveats. Japanese martial arts experts, including instructors from the very school that informed the game’s motion capture, have recreated the technique on video, proving it’s not pure fantasy. But historical context, physics, and practical risks add layers to why this “surprise” lands with such impact. We’ll break it down step by step, drawing from expert analyses, historical records, and community recreations to separate the myth from the steel.

Atsu’s Back Draw: Breaking Down the Game’s Signature Move

In Ghost of Yōtei, the odachi (or ōdachi, meaning “great sword”) is unlocked early via the “The Way of the Odachi” quest in Yotei Grasslands, where Atsu trains under a wandering sensei to master its weighty arcs against brute enemies. Clocking in at up to 150 cm (nearly 5 feet) long and weighing 1.5–3 kg, it’s too cumbersome for hip carry—hence the back mount, a nod to historical battlefield logistics where retainers often hauled such behemoths. Drawing from the hip? Impossible without contorting like a pretzel. So Atsu adapts: She reaches over her shoulder, pulls the scabbard (saya) free, gives it a slight upward flick to expose the hilt, grips the blade’s flat midway to control its descent, and rotates it into a ready stance—all in under two seconds of animation.

This isn’t arbitrary flair. Sucker Punch consulted Tenshinryū practitioners for motion capture, ensuring the odachi’s sway and heft feel authentic. The game’s physics simulate the blade’s momentum, with haptic feedback rumbling your DualSense controller as it “catches” in Atsu’s palm. But when X user @ikazombie posted a clip questioning its realism—”How does she not slice her own face off?”—it sparked a viral storm. Responses flooded in: videos of experts mimicking the draw, debates on iaijutsu (quick-draw arts), and even physics breakdowns on Reddit. The consensus? It’s grounded in tradition, but amplified for spectacle.

Real-Life Recreations: When Experts Step Up

The surprise hits hardest in the recreations. Dofu Takizawa, a 157 cm-tall instructor from Tenshinryū Hyōhō—the same school behind Yōtei‘s swordplay—uploaded a video on October 10 showing him nailing the unsheathing and blade-catch with a 90 cm, 1.5 kg odachi. Standing in a dojo, he reaches back fluidly, extracts the sword, and snags the flat mid-air with his off-hand, transitioning to a low guard without a hitch. “It’s not impossible,” Takizawa told Automaton Media, “but it demands precision—any wobble, and you’re cut.” His sheathing? Less graceful—he crouches to slot it home, unlike Atsu’s upright spin. Still, it’s a win for realism.

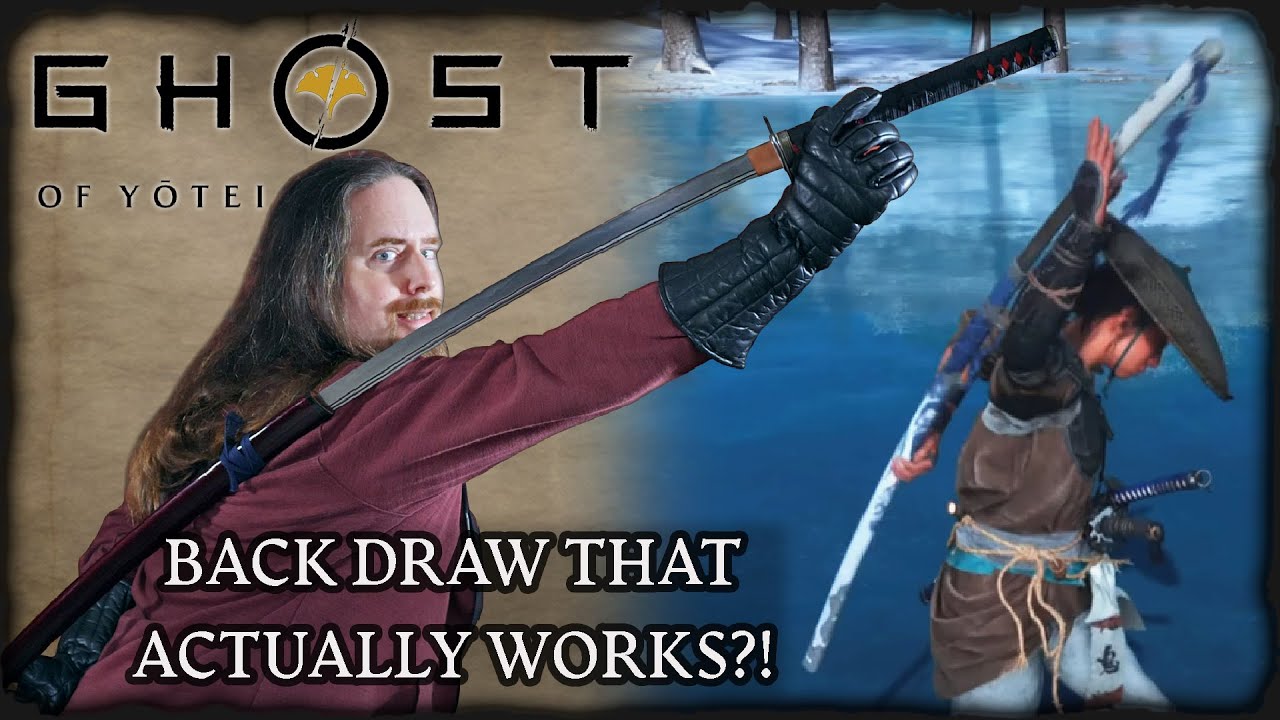

X user @lornplum echoed this, posting a clip of his own back draw: “The game’s touch of holding the blade for length control is brilliant realism.” Total Apex Gaming analyzed similar demos, noting practitioners use the blade’s flat (non-sharpened spine) to avoid self-injury, a technique rooted in tameshigiri (test cutting) drills. YouTube’s “Does the Back Draw from GHOST OF YŌTEI Work in REAL LIFE?” (racking up 500K views in days) features a kendo master timing it at 1.8 seconds—faster than a standard iaijutsu hip draw.

These aren’t cherry-picked; forums like r/Ghostofyotei buzz with user videos, from amateurs fumbling hilts to pros chaining draws into katas. IGN consulted iaido experts, who scored it 8/10 for feasibility: “Cool as hell, and viable in a pinch.”

Historical Roots: From Battlefield Beasts to Iaijutsu Shadows

Odachi weren’t desk ornaments—they were anti-cavalry terrors from the Nanbokuchō period (1336–1392), wielded by foot soldiers to unhorse mounted foes. Too long for the waist (over 3 shaku, or 90 cm), they were slung across the back or shouldered like spears, drawn only when committed to sweeping arcs. Wikipedia notes retainers often carried them, handing them over for use—practicality over solo swagger.

Enter iaijutsu: the combative quick-draw art predating iaido (its modern, meditative form from the 1930s). Born in the 15th century alongside kenjutsu (unsheathed fighting), iaijutsu emphasized nukitsuke—drawing while pulling the saya back (saya-biki)—for surprise strikes. Schools like Musō Jikiden Eishin-ryū trace to Hayashizaki Jinsuke (late 1500s), focusing on seated or standing draws against ambushes. Back draws? Rare, but documented for nodachi in battlefield scrolls, where warriors flipped blades mid-extraction to counter length.

r/iaido threads dissect the physics: The back draw leverages torque from the shoulder pivot, but gravity fights you—hence the flick to “earn length,” as @lornplum put it. TV Tropes nods to its rarity in media, but real koryū (ancient schools) teach variants for oversized blades. Darrell Max Craig’s Drawing the Samurai Sword details similar drills, stressing blade-flat grips to prevent slips.

Aspect

In-Game (Atsu)

Real Life (Tenshinryū/Iaijutsu)

Feasibility Score (1-10)

Carry Position

Back sling for mobility

Historical for nodachi; awkward for daily use

9 – Practical on battlefield

Unsheathe Speed

~1.5 seconds animated

1.8–2.5 seconds in demos

8 – Momentum helps, but risky

Blade Catch

Flat grip, no cut

Flat only; edge risks laceration

7 – Doable with practice

Sheathing

Upright flourish

Often crouched; standing rare

5 – Game’s stylized for cool

Combat Utility

Stagger opener vs. brutes

Anti-cavalry sweeps; not quick duels

9 – Devastating if landed

The Caveats: Why It’s a Gamble, Not Gospel

Here’s the rub: While doable, it’s no everyday iaido staple. Odachi were niche—maybe 1% of samurai arsenals—phased out by the Edo period for lighter katana. Back draws shine in open fields, not tight quarters; one Reddit physicist crunched the torque: “At 1.5 kg, a mid-air fumble equals a face full of steel.” Global News’ iaido segment with Sensei Jim Wilson highlights timing’s peril: “One motion defeats foes—or yourself.”

r/SWORDS users debunk Hollywood myths: No widespread back sheaths for quick draws; hip was king for iaijutsu speed. Modern iaido bans live blades for safety, focusing on form over fury. Yet Yōtei‘s version? A “brilliant touch,” per experts—blending history with heroism.

The Verdict: Game On, But Train First

The back draw works in real life—kind of. It’s a feasible flourish for the trained, rooted in iaijutsu’s shadows and Tenshinryū’s steel, but demands dojo-honed precision over Atsu’s effortless cool. As IGN put it, “Impossibly cool, but (kind of) doable.” With Yōtei‘s 87 Metacritic glow and 2026 co-op DLC looming, Sucker Punch proves games can honor history while hacking its edges. Surprise? It’s more real than you think—but don’t try at home without a sensei. Ezo’s ghosts approve.