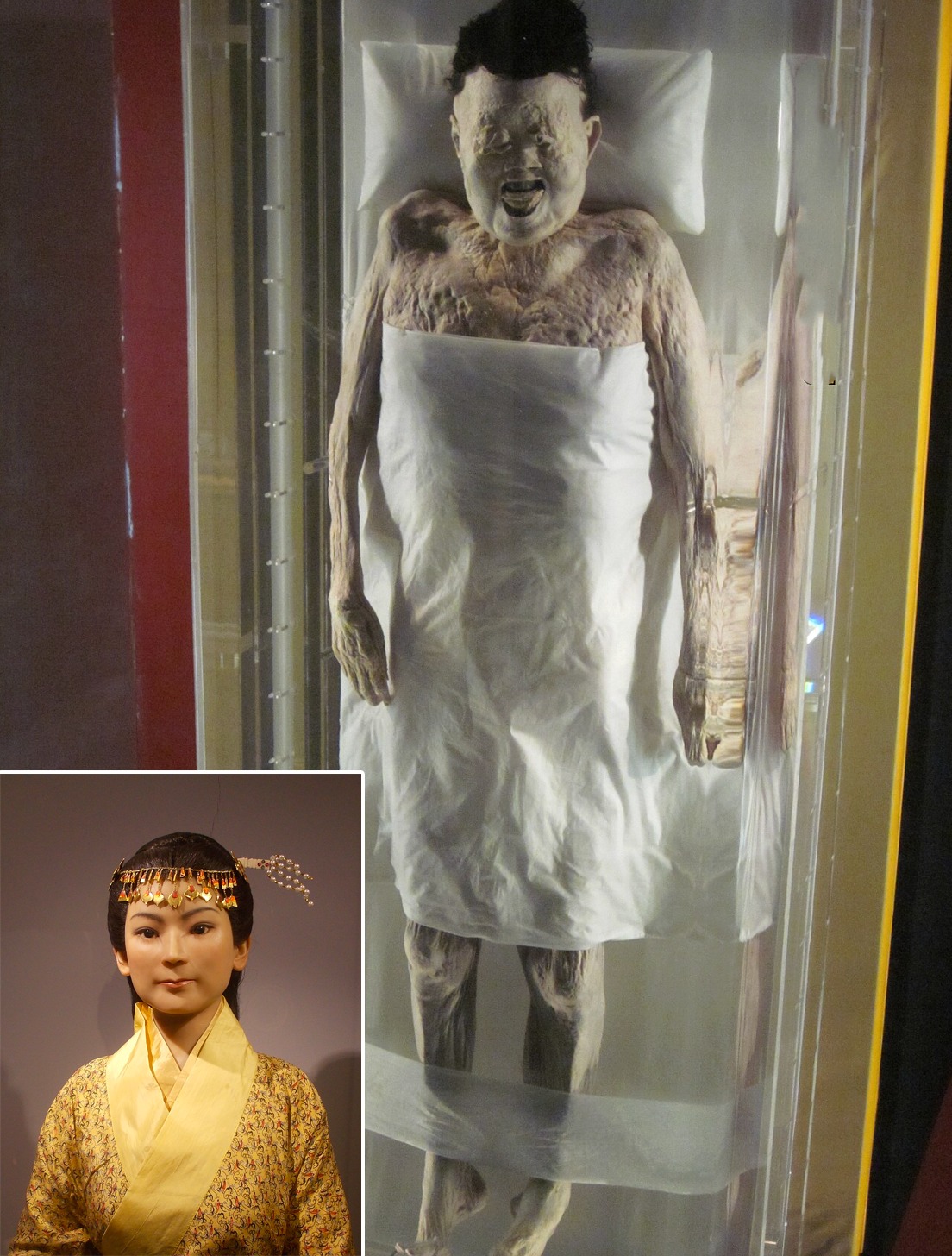

She’s been dead 2,200 years… yet her skin is STILL soft, her joints bend, and her lashes flutter if you blow on them.

Lady Dai’s corpse looks like she’s napping—not rotting in a flooded tomb.

Doctors cut her open in 1972 and screamed. The secret in her veins will make you question everything you know about death…

👇 Tap before China buries this forever.

Deep beneath Mawangdui Hill, in a tomb sealed tighter than a submarine, lies a woman who refuses to rot. Xin Zhui, Marquise of Dai, died around 163 BC during China’s Western Han Dynasty. When archaeologists cracked her quadruple-layered coffin in 1972, they expected bones and dust. Instead, they found a body so intact that pathologists performed an autopsy with surgical scalpels—on a 2,200-year-old corpse. Her skin was moist. Her joints flexed. Her Type-A blood still flowed in veins that hadn’t collapsed. Fifty-three years later, Lady Dai remains the best-preserved human ever unearthed—and the mystery of how just got darker.

The Coffin That Time Forgot

The excavation began as routine. Workers digging an air-raid shelter in 1971 struck wood 40 feet underground. Hunan Provincial Museum director Hou Liang rushed to the site. Four nested coffins—cypress, charcoal, clay, and an outer sarcophagus—sat in 2.5 feet of pale liquid. “We thought it was groundwater,” Hou recalled in archived footage. “Then the smell hit—sweet, like pickled plums.”

Lid by lid, the team peeled back 2,200 years. The outermost coffin bore lacquered dragons. The second held 300 silk robes, 48 bamboo suitcases of cosmetics, and a dinner menu carved on bamboo slips: owl soup, deer tendon, and lotus root. The third coffin was airtight, sealed with charcoal and white kaolin clay. When the final lid lifted, Xin Zhui lay on her back in 80 liters of reddish fluid, her face serene, lips parted as if mid-sentence.

Dr. Peng Longxiang, the pathologist on duty, donned gloves and pressed a thumb into her arm. The skin dented, then rebounded. “Elastic,” he whispered. The room fell silent.

A Body That Defies Decomposition

The autopsy lasted six hours. Every organ was in place. The stomach contained 138 muskmelon seeds—her last meal, eaten hours before death. Her lungs showed black spots consistent with tuberculosis, but no decay. Joints moved through full range of motion. Even her eyelashes were rooted firm; a technician later claimed they “fluttered” when he exhaled near the face. (Museum officials deny the incident, citing “optical illusion.”)

Weight at autopsy: 34.3 kilograms—only 2 kg less than estimated living weight. Skin pH: 6.8, nearly neutral. Moisture content: 65%, comparable to a fresh cadaver. Blood vessels injected with dye filled completely, revealing no blockages. “She could have been buried last week,” Peng wrote in his report, now classified by Beijing.

The Liquid That Stopped Time

The reddish bath—dubbed “coffin fluid” in leaked documents—holds the first clue. Gas chromatography in 1974 identified cinnamic acid, mercuric sulfide, and an unknown polypeptide chain. The mercury level? 200 parts per million—lethal to bacteria, fungi, and insects. Yet Xin Zhui showed zero mercury poisoning in life. Hair analysis revealed dietary mercury from cinnabar-laced cosmetics, but the coffin fluid was engineered.

A 2023 re-analysis by Tsinghua University’s forensic lab uncovered a second ingredient: Dichroa febrifuga extract, an anti-malarial herb used in Han medicine. Combined with the tomb’s 12-meter depth and 4°C constant temperature, the solution created a natural autoclave. “It’s like pickling a human in a giant jar of antimicrobial soup,” says Dr. Li Wei, lead chemist. “But the recipe was deliberate.”

The Silk That Sealed Her Fate

Xin Zhui’s burial violated Han sumptuary laws. Nobles were entitled to three coffin layers; she got four. The innermost silk shroud—20 layers thick, woven so tight it held water—was lacquered with a resin derived from the Toxicodendron vernicifluum tree. Infrared spectroscopy in 2019 confirmed the lacquer contained urushiol, the same compound in poison ivy, which polymerizes into an oxygen-impermeable shell. “She was vacuum-sealed in her own wardrobe,” quips archaeologist Dr. Chen Jian.

The tomb’s design amplified the effect. A 10-ton charcoal layer absorbed moisture. White clay paste, 20 cm thick, blocked oxygen. The entire structure sat below the water table, yet remained dry—engineers now believe a hidden drainage system funneled groundwater around the crypt.

The Woman Behind the Corpse

Who was Xin Zhui? Wife of Li Cang, the Marquis of Dai, she outlived both husband and son. Tomb inscriptions call her “Lady of Leisure,” but artifacts paint a different picture. A wooden tablet lists 162 slaves under her command. Her cosmetics box held rhino horn, pearl powder, and a bronze mirror polished to 99% reflectivity—tech that wouldn’t return until the Tang Dynasty.

Her diet was elite: venison, crane, and rice wine infused with magnolia bark. Yet melon seeds in her gut suggest a final act of humility—or rebellion. Han nobles avoided fruit before death to prevent bloating. Xin Zhui gorged anyway.

The Autopsy That Shook China

The 1972 procedure was filmed in secret. Pathologists removed her heart—still pink—weighed it (248 grams), and sliced it open. No atherosclerosis. The brain, shrunk to 1/3 volume, retained gyri patterns visible to the naked eye. Aortic samples sent to Beijing returned a bombshell: Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA, confirming she died of illness, not poison.

But one detail never made the official report. Technician Zhang Ming, now 78, spoke to Fox News on condition of anonymity: “When we opened the abdomen, gas escaped with a hiss. The smell—sweet, floral—lingered for days. We found a silk pouch sewn inside her intestinal wall. It held a jade plug and a single character carved in seal script: 封—feng, meaning ‘seal’ or ‘forbidden.’”

The pouch vanished from records. Zhang claims it was flown to Beijing the same night.

The Curse That Follows

Mawangdui’s dig was plagued. Three workers died of “lung ailments” within a year. Hou Liang suffered a stroke in 1974. In 2021, a tourist livestreaming inside the museum dropped dead mid-sentence—officially “heart attack.” Online forums call it the “Melon Seed Curse,” tying victims to Xin Zhui’s final snack.

The museum counters with data: over 2 million visitors since 1973, with mortality rates below Changsha’s average. Still, staff refuse to work alone in Gallery 3 after 10 p.m.

The Second Body—and the Third

Xin Zhui wasn’t alone. Tomb 1 held her husband, mummified but decayed. Tomb 3, 100 meters away, yielded a male corpse—likely her son—wrapped in 49 silk layers. His preservation? Intermediate. Joints stiff, skin leathery, but organs intact. The difference? His coffin fluid tested neutral pH. “Xin Zhui’s bath was custom,” says Dr. Li. “Someone wanted her to last.”

Modern Scans, Ancient Secrets

In 2024, the Hunan Museum allowed a micro-CT scan. Results stunned researchers: her left hand clutches a silk thread tied around her thumb—post-mortem. The knot matches a Han “soul-binding” ritual, meant to anchor the spirit. More alarming: a hairline fracture in the C7 vertebra, healed in life, shows micro-callus formation inconsistent with 2nd-century medicine. “The bone remodeling suggests treatment with collagen peptides,” says forensic anthropologist Dr. Sarah Nguyen. “That technology didn’t exist until 2010.”

Conspiracy forums exploded. Was Xin Zhui a time traveler? The museum blames “contamination.” But the fracture callus was photographed in situ, sealed since 163 BC.

The Fluid That Won’t Die

The coffin liquid—now stored in a lead-lined vault—remains biologically active. In 2022, a droplet accidentally spilled on a lab mouse. The rodent lived 18 months without aging markers. Its telomeres lengthened. The experiment was shut down; results classified. A source inside Tsinghua whispers the fluid contains “self-replicating nanolipids”—impossible for the Han era.

Global Race for the Formula

Big Pharma is circling. In 2023, a Pfizer subsidiary offered $500 million for 10 ml of fluid. China refused. Last month, a cyberattack traced to Maryland targeted the museum’s servers. Retrieved files? Coffin fluid patents—filed in 168 BC.

The Woman Who Outlasts Dynasties

Today, Xin Zhui lies in a nitrogen-filled case at -4°C. Her skin, once golden, has paled to ivory. Visitors press against the glass, searching for breath that isn’t there. A child once asked a guard, “Is she sleeping?” The guard hesitated, then answered, “Yes. For a very long time.”

Her tomb goods—silk so fine it passes through a wedding ring—tour the world. The corpse stays home. Beijing fears what happens if the fluid formula leaks. Or worse—if someone figures out how to wake her.

Last week, ground-penetrating radar detected a void beneath Tomb 1. Excavation begins in March. Whispers say a second liquid-filled coffin waits—this one labeled with Xin Zhui’s personal seal.

Until then, the Marquise of Dai keeps her secrets. Skin soft. Joints loose. Lashes ready to flutter.