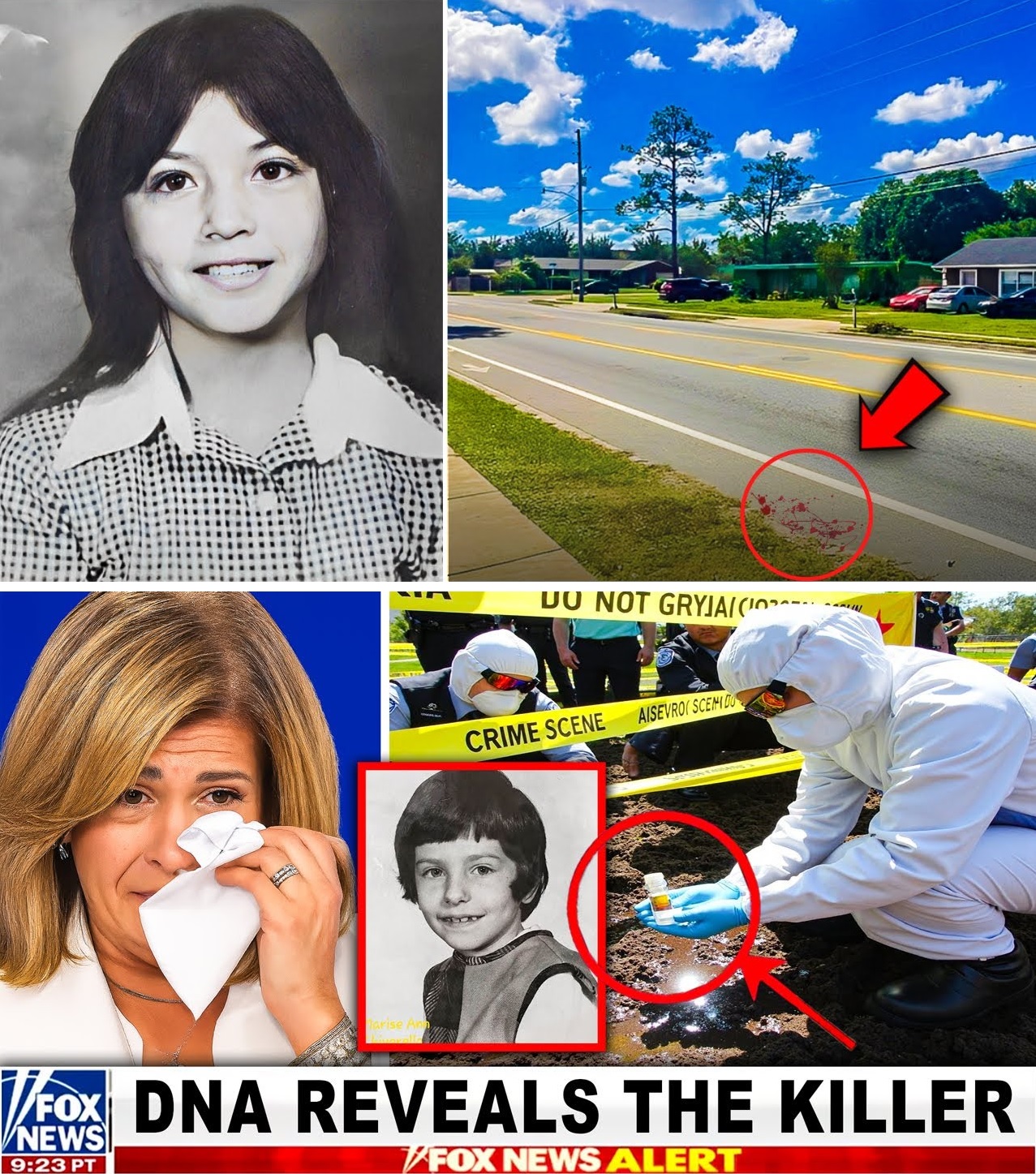

After 50 Years They Finally Solved The Marise Chiverella Case — And the Details Are Horrifying 😱

Imagine a 9-year-old girl skipping to school with canned goods for her teacher, only to vanish into a nightmare of abduction and brutality. Nearly 58 years later, DNA cracks the silence: a local bartender’s savage assault in a coal pit, her tiny body discarded like trash. This isn’t justice—it’s a gut-wrenching reminder of evil lurking in quiet streets.

The chilling confession that haunted a town:

On a crisp March morning in 1964, 9-year-old Marise Ann Chiverella waved goodbye to her family and set off for St. Joseph’s Parochial School, clutching canned goods for her teacher. By afternoon, her lifeless body lay discarded in a coal-stripping pit turned dump, her innocence shattered by a brutal sexual assault and strangulation. For nearly 58 years, the murder haunted the tight-knit coal town of Hazleton, Pennsylvania—a case so raw it etched itself into the community’s soul, with over 250 investigators poring through 4,700 pages of files but yielding no answers. Then, in a February 2022 announcement that rippled through cold case circles, Pennsylvania State Police revealed the killer: James Paul Forte, a 22-year-old bartender who lived just blocks from the Chiverellas. Identified through cutting-edge genetic genealogy and the dogged work of a 20-year-old college student, Forte’s DNA—extracted from his exhumed remains—matched semen stains on Marise’s jacket. The details, once buried in investigative vaults, now paint a horrifying portrait of predatory violence: a child lured from her path, violated in broad daylight, and dumped like refuse. As the case marks its 61st year, it stands as Pennsylvania’s oldest solved via DNA tech, a bittersweet victory that exposes the fragility of small-town safety and the relentless march of forensic science.

Marise Ann Chiverella was the picture of childhood joy in 1964 Hazleton, a blue-collar enclave in Luzerne County where anthracite mines scarred the hills and Catholic families like hers anchored the neighborhoods. Born on August 15, 1954, to Carmen and Mary Chiverella, she was the fourth of seven siblings in a modest home on North Wyoming Street. With her dark curls, bright eyes, and a penchant for jump-rope and playing the organ at church, Marise dreamed of becoming a nun—a fitting aspiration for the devout girl who attended Mass daily. “She was our little angel,” her sister Carmen Marie Radtke later recalled at a 2022 press conference, her voice trembling with the weight of decades. “Always helping, always smiling.” On March 18, that innocence propelled her out the door at 8 a.m., a short 10-block walk to school. She carried two cans of vegetables—donations for a class project—her plaid skirt swishing as she hurried to make morning Mass. Witnesses last saw her near West Fourth and North Church streets around 8:10 a.m., chatting amiably. Then, silence.

Panic set in by noon. Marise’s teacher, Sister Mary Immaculata, alerted the family when she didn’t arrive. Carmen Chiverella, a factory worker, rushed home from her shift; Mary, a homemaker, scoured the streets. Neighbors joined the hunt, combing alleys and backyards in a town unaccustomed to such dread—Hazleton’s crime rate was low, its streets safe for kids. At 1 p.m., horror unfolded: A local man, teaching his 16-year-old nephew to drive on a dirt road in Hazle Township, spotted what looked like a “large doll” in a 20-foot-deep coal pit, a reclaimed strip-mine site used as an illegal dump. Drawing closer, they realized it was a child’s body—Marise’s, partially clothed, her face bruised, her small frame twisted in the mud. Pennsylvania State Police arrived within minutes, the pit’s steep walls complicating recovery. An autopsy at Hazleton General Hospital confirmed the unimaginable: Marise had been abducted, dragged over two miles, sexually assaulted, and strangled—likely with her own clothing or bare hands. Semen stains marred her jacket; scratches and bruises suggested a desperate struggle. “It was the stuff of nightmares,” retired Trooper Frank Good, who worked the initial scene, said in 2022. “A little girl, violated and left like garbage.”

The investigation exploded into overdrive. Over 100 troopers from Troop N descended on Hazleton, canvassing 5,000 homes, interviewing 1,200 suspects, and chasing tips from as far as New York. The pit yielded no murder weapon, but fibers from Marise’s clothing traced to local soil. Polygraphs, hypnosis sessions, and suspect lineups filled the files, but leads evaporated. Early theories swirled: a transient miner, a jealous relative, even a satanic cult—fueled by the era’s Red Scare paranoia. James Paul Forte, then 22, lived six blocks from the Chiverellas at 28 W. Chapel Street, working nights as a bartender at the V.F.W. Post 1890. A high school dropout with a quiet demeanor and no criminal record, he blended into the mill-town fabric—unmarried, living with his parents, a fixture at local dives. Neighbors described him as “odd but harmless,” though whispers of peeping tom complaints surfaced years later. Yet in 1964, he passed initial questioning without suspicion. “He was one of thousands we cleared,” Cpl. Mark Baron, the lead investigator in 2022, noted. The case went cold by summer, classified unsolved amid mounting pressure—Hazleton’s mayor offered a $1,000 reward, but grief lingered. Marise’s funeral at St. Mary’s Church drew 2,000 mourners; her casket, white and flower-draped, symbolized a community’s shattered trust.

Decades dragged on, the wound festering. Carmen and Mary Chiverella died without answers—Carmen in 1993, Mary in 2001—clinging to a ritual: At Sunday dinners, Mary would end grace with, “Please help the Pennsylvania State Police find the man who hurt my daughter.” Siblings Ronald, Carmen Marie, and others raised awareness, funding billboards and tips lines. The case morphed into folklore: “Marise’s Ghost” tales scared neighborhood kids; annual memorials at the pit site (now a wooded lot) drew locals. Investigators rotated—250 in total, from Trooper Good in 1964 to digital sleuths in the 2000s—but progress stalled until DNA tech evolved. In 2007, Pennsylvania’s state lab extracted a partial profile from semen on Marise’s jacket, a breakthrough from fluids preserved in the pre-DNA era. It sat unused until 2018, when budget cuts nearly shelved it. Enter Parabon NanoLabs, a Virginia firm specializing in investigative genetic genealogy (IGG)—the same method cracking cases like the Golden State Killer. Parabon built a suspect composite: a white male, early 20s, with Italian or Eastern European roots. In 2019, they uploaded the profile to public databases like GEDmatch, yielding a distant cousin match.

The pivotal turn came in 2020 with Eric Schubert, then an 18-year-old Elizabethtown College student and genealogy whiz. Volunteering via the DNA Detectives Facebook group, Schubert dove in, constructing a sprawling family tree from the cousin hit—over 1,000 names, cross-referenced with 1964 Hazleton census data, obituaries, and voter rolls. “It was like solving a massive puzzle,” he told NPR in 2022. Weeks of late nights narrowed it to Forte, deceased in 1980 at age 38 from a heart attack. No priors, but his proximity and timeline fit: single, night shifts leaving mornings free. Police exhumed his body from St. Mary’s Cemetery on January 25, 2022—his widow, remarried, consented reluctantly. Dental records confirmed identity; tissue samples matched the jacket DNA at 99.999% certainty. “Conclusive,” Baron declared at the February 10 press conference, flanked by Good (now 90) and Marise’s siblings. Radtke, reading Bible verses on vengeance and child harm, said, “Justice has been served today.”

The revelation stunned Hazleton. Forte, remembered as a “drinking buddy” at the V.F.W., left no confession—his 1980 obit painted him as a “loving son.” But the details horrified: Autopsy photos, unsealed in 2022, showed ligature marks from her own scarf; the assault, per forensic reconstruction, occurred pre-strangulation, suggesting prolonged terror. No motive surfaced—opportunistic predation in a town of 30,000, where kids walked alone. The case’s solving via IGG sparked national buzz: CNN dubbed it Pennsylvania’s oldest DNA breakthrough; The New York Times profiled Schubert, now a 23-year-old genealogist. Yet closure eluded. “We have the who, but not the why,” Ronald Chiverella said. Families grappled: Radtke spoke of “emptiness,” vowing to honor Marise through scholarships for St. Joseph’s students. The pit site, reclaimed in the 1970s, now hosts a memorial plaque—flowers and teddy bears pile up annually.

Broader ripples reshaped cold case work. Pennsylvania allocated $1 million in 2023 for IGG across 50 cases; nationally, the FBI’s CODIS database integrated genealogy uploads. Schubert’s role inspired youth: “One click can change history,” he lectures at colleges. But horrors persist—Hazleton’s 2024 unsolved cases include a 1972 child abduction. Experts like Dr. CeCe Moore of Parabon warn of ethical pitfalls: privacy invasions in databases, false positives. Still, for Marise’s kin, it’s validation. “Mom prayed for this,” Ronald said. As 2025 unfolds, the Chiverella file—now digitized—serves as a testament: Science can unearth buried evil, but some scars defy healing. In Hazleton’s fading coal shadows, Marise’s story endures—not as tragedy, but triumph over time’s cruel silence.