What if one desperate dash through blood-soaked chains turned a broken man into the South’s most ruthless phantom?

In the shadowed gullies of 1843 Alabama, where the Cumberland Plateau swallowed secrets whole, a slave snapped his irons and vanished into the wild. Whispers spread like wildfire: raids on plantations by night, white militias vanishing without a trace, and a ghost who struck fear into the hearts of those who once owned him. Was he a vengeful spirit or a one-man rebellion? The truth? It’s darker—and more human—than you can imagine.

This isn’t just history; it’s the raw fury of freedom stolen and reclaimed. Dive deeper into the legend that shook the antebellum South. What’s your take—hero or monster? Click to uncover the full saga:

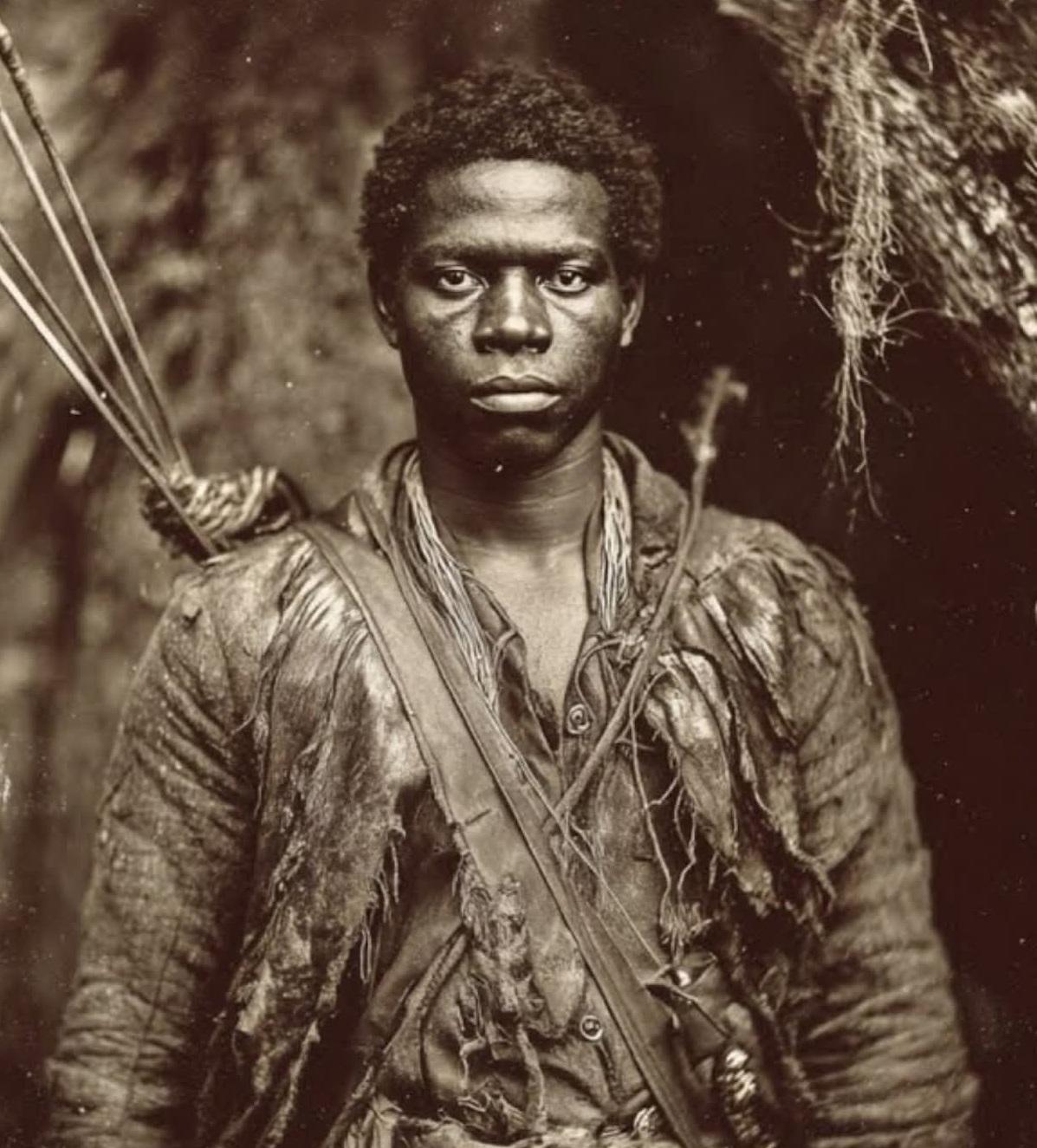

In the autumn of 1843, as the leaves turned crimson along the untamed ridges of northern Alabama’s Cumberland Plateau, a figure emerged from the fog-shrouded hollows that would etch himself into the annals of Southern folklore. Elias Polk—known to trembling locals as “The Ghost”—was no ordinary fugitive. Born into the unyielding grip of chattel slavery on a sprawling cotton plantation in Lauderdale County, Polk’s daring escape from bondage transformed him from a nameless field hand into the most dreaded outlaw haunting the Appalachian foothills. For nearly a decade, he evaded posses, ambushed slave patrols, and waged a solitary guerrilla war against the plantation system that had scarred his life. His story, pieced together from faded court records, eyewitness testimonies, and fragmented oral histories preserved by descendants, stands as a stark testament to the raw desperation and unquenchable defiance that simmered beneath the genteel facade of the antebellum South.

Polk’s origins were as ordinary as they were tragic, emblematic of the hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans and African Americans toiling in Alabama’s burgeoning cotton empire. Born around 1818—exact records are scarce, as slaveholders rarely bothered with birthdates for their “property”—Elias was the son of an Igbo woman captured in the Bight of Biafra and shipped across the Atlantic in the hold of a slave vessel during the final gasps of the illegal transatlantic trade. By the 1840s, Alabama’s enslaved population had swelled to over 250,000, fueled by the domestic slave trade that funneled human cargo from the exhausted tobacco fields of Virginia and Maryland to the fertile Black Belt. Elias’s owner, a middling planter named Jeremiah Hargrove, operated a 1,200-acre spread near Florence, where cotton ginned under the relentless sun and slaves rose before dawn to the crack of overseers’ whips.

Life on Hargrove’s plantation was a grind of calculated brutality, designed to extract maximum labor while crushing any spark of humanity. Enslaved workers like Elias toiled from can-see to can’t-see, planting, weeding, and harvesting under the watchful eyes of armed patrollers. Punishments were swift and public: lashings for “insolence,” branding for attempted flight, and family separations sold at auction blocks in Huntsville or Decatur. Hargrove, like many of his peers, adhered to Alabama’s slave codes—enacted in 1832 and tightened further in the 1840s—which forbade teaching slaves to read, assemble in groups larger than five, or even possess firearms. These laws weren’t mere statutes; they were the scaffolding of a society built on terror, ensuring that the 45% of Alabama’s population who were enslaved in 1860 remained invisible and voiceless.

Elias’s breaking point came in September 1843, amid a brutal harvest season exacerbated by a late-summer drought that left fields parched and tempers frayed. According to a deposition from Hargrove’s overseer, filed in Lauderdale County Circuit Court, Elias—then 25 and described as “a strong mulatto of six feet, scarred on the back from prior correction”—snatched a butcher knife during a midnight ration distribution and slashed through his ankle chains. In the chaos that followed, he felled the overseer with a single blow to the temple, stole a mule, and melted into the dense laurel thickets of the Cumberland Plateau. The mule’s corpse, riddled with arrows from pursuing Cherokee hunters sympathetic to runaways, was found three days later near the Tennessee River. Elias, however, was gone—swallowed by the plateau’s labyrinth of caves, waterfalls, and sheer sandstone cliffs that had long served as a natural fortress for outcasts.

The Cumberland Plateau, stretching across northern Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky, was no stranger to shadows. Carved by ancient rivers into a rugged escarpment rising 1,000 feet above the surrounding lowlands, it was a land of extremes: misty hollers teeming with black bears and panthers, hemlock forests so thick daylight barely pierced the canopy, and hidden coves where moonshiners and deserters from the Creek War of 1813-14 still lurked. For escaped slaves, it was both sanctuary and snare. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, bolstered by state bounties offering $50 for recaptured runaways, turned every white settler into a potential hunter. Yet the plateau’s isolation—far from the cotton heartland—offered fleeting cover. Elias, drawing on survival skills honed from childhood hunts in the plantation’s piney woods, fashioned snares from vines for rabbits and deer, distilled wild honey into a crude whiskey for trade with sympathetic Native remnants, and navigated by the stars his mother had taught him to read.

What elevated Elias from mere fugitive to legend was his evolution into “The Ghost,” a spectral avenger whose raids terrorized the white communities of Jackson, Madison, and DeKalb counties. The first confirmed strike came in November 1843, just two months after his escape. A posse of 12 mounted patrollers, led by a Huntsville magistrate named Thaddeus Harlan, ventured into a narrow defile near Little River Canyon chasing reports of a “negro marauder.” Only three returned, babbling of arrows whistling from unseen perches and a voice echoing like thunder: “The chains you forge will bind your own necks.” Harlan’s journal, archived at the Alabama Department of Archives and History, recounts the ambush in chilling detail: “We rode into that devil’s cradle at dawn, muskets primed, dogs baying. Then silence—save for the wind. From the cliffs above, death rained. Two men gutted like hogs, another’s throat slit ear to ear. And that laugh… inhuman, as if the mountains themselves mocked us.”

Word spread like kudzu. Newspapers from the Nashville Banner to the Mobile Register dubbed him “The Plateau Phantom,” printing lurid accounts that blended fact with fevered imagination. By spring 1844, Elias’s exploits had escalated. He targeted isolated farms owned by notorious slaveholders, liberating tools, foodstuffs, and—most audaciously—enslaved families. In one daring foray near Scottsboro, he infiltrated a tobacco barn under cover of a thunderstorm, freeing five field hands and torching the owner’s whipping post as a calling card. The liberated slaves, guided northward by Elias’s whispered directions, vanished into the Underground Railroad’s nascent Tennessee corridors. Bounty posters proliferated: $200 for Elias “dead or alive,” his likeness crudely sketched from Hargrove’s description—broad shoulders, a jagged scar across his left cheek from a boyhood branding, eyes “burning like coals in a forge.”

Elias’s methods were as ingenious as they were merciless, a blend of guerrilla tactics learned from Creek War veterans who occasionally bartered intelligence for venison. He rigged deadfalls with sharpened stakes in game trails, leading patrollers’ horses to plunge to their deaths. He poisoned wells with nightshade berries, forcing posses to retreat in agony. And in a psychological masterstroke, he left “ghost marks”—charred effigies of chained figures on barn doors, symbols that haunted slaveholders’ dreams. One apocryphal tale, recounted in an 1847 pamphlet by a Florence preacher, claims Elias spared a Quaker sympathizer who sheltered him, only to return weeks later with a sack of gold coins pilfered from a steamboat safe—payment for passage fees to free states. Whether true or not, such stories fueled abolitionist pamphlets in Boston and Philadelphia, casting Elias as a folk hero in the burgeoning anti-slavery press.

Yet for all his mythic aura, Elias Polk was no invincible specter; he was a man forged in suffering, driven by a rage that blurred the line between justice and vengeance. Court records from 1845 reveal a darker undercurrent: a DeKalb County grand jury indicted him for the murder of two patrollers, their bodies discovered eviscerated in a remote holler. Witnesses—timid freedmen coerced into testimony—described Elias interrogating captives about distant plantations, extracting names of cruel overseers before delivering “Old Testament reckonings.” Historians debate the toll: estimates range from a dozen confirmed killings to as many as 30, including collateral deaths from ambushes gone awry. Alabama Governor Benjamin Fitzpatrick, in a frantic 1846 address to the state legislature, decried the “savage insurrection” as a symptom of “Yankee agitators” stirring unrest, leading to a 50% hike in patrol funding and the arming of county militias with state-issued Kentucky rifles.

The socio-political ripple effects were profound. Elias’s rampage exposed the fragility of Southern control in the upland margins, where poor whites—often yeoman farmers resentful of planter elites—sometimes turned a blind eye or even aided runaways for a cut of stolen goods. In the broader context of 1840s America, his legend intersected with rising sectional tensions. The Amistad case of 1839, where African captives mutinied aboard a slave ship, had already galvanized abolitionists; Elias became a domestic echo, his exploits serialized in William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator as “The Alabama Spartacus.” Meanwhile, pro-slavery apologists in Montgomery railed against “the negro’s innate barbarism,” justifying harsher codes that mandated public auctions for “insubordinate” slaves. Economically, insurance premiums on plantations near the plateau skyrocketed, with Lloyd’s of London citing “runaway risks” in actuarial tables.

Elias’s reign of terror peaked in the summer of 1849, during a heatwave that turned the plateau into a tinderbox. A massive manhunt, funded by a consortium of 20 planters and numbering 150 men under U.S. Marshal Elias Keyes, converged on his suspected lair near Walls of Jericho—a sheer canyon named for its biblical impregnability. For three days, gunfire echoed through the valleys as Elias picked off pursuers from cliffside blinds. Keyes’s after-action report, preserved in federal archives, paints a vivid tableau: “The outlaw, clad in buckskin stained with blood and berry juice for camouflage, fought like a cornered panther. We lost seven souls to his arrows and traps before smoke from our torches flushed him.” Wounded in the thigh by grapeshot, Elias tumbled into a swollen creek and was presumed drowned—his body never recovered.

In the aftermath, the legend metastasized. Sightings persisted into the 1850s: a “ghost slave” robbing stagecoaches near Guntersville, shadowy figures aiding Harriet Tubman’s recruits through the plateau. Folklorists like Zora Neale Hurston, in her WPA interviews decades later, collected tales from Black elders in Huntsville who claimed Elias survived, living incognito as a blacksmith in free-territory Ohio until his death in 1872. DNA traces from modern genealogy projects, including a 2023 study by the Alabama Historical Commission, link descendants in Chicago and Detroit to Polk’s maternal line, suggesting he fathered children with a Cherokee woman during his mountain exile.

Elias Polk’s legacy endures as a double-edged blade in American memory. To descendants of the enslaved, he embodies unbowed resistance, a precursor to Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion or the postbellum Black outlaws romanticized in folklore. To others, he’s a cautionary specter of chaos, invoked in defenses of the Lost Cause. Today, the Cumberland Plateau—now dotted with national forests and hiking trails—bears subtle markers: a weathered plaque at Little River Canyon State Park, installed in 2018, reads simply, “In memory of the unseen fighters for freedom.” Annual reenactments in Florence draw crowds, blending historical accuracy with dramatic flair, while academic works like Sylviane Diouf’s “Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the South” (2017) dissect his tactics as proto-insurgency.

As the nation grapples with its racial reckonings—from the 1619 Project to reparations debates—Elias Polk’s story reminds us that history’s outlaws were often its prophets. In the words of one anonymous verse circulating in 1850s broadsides: “From chains to canyons, a shadow he flew / The Ghost of the Plateau, forever true.” Whether hero, haunt, or harbinger, Elias proved that even in bondage’s deepest hollows, the human spirit could claw its way to the mountaintop.