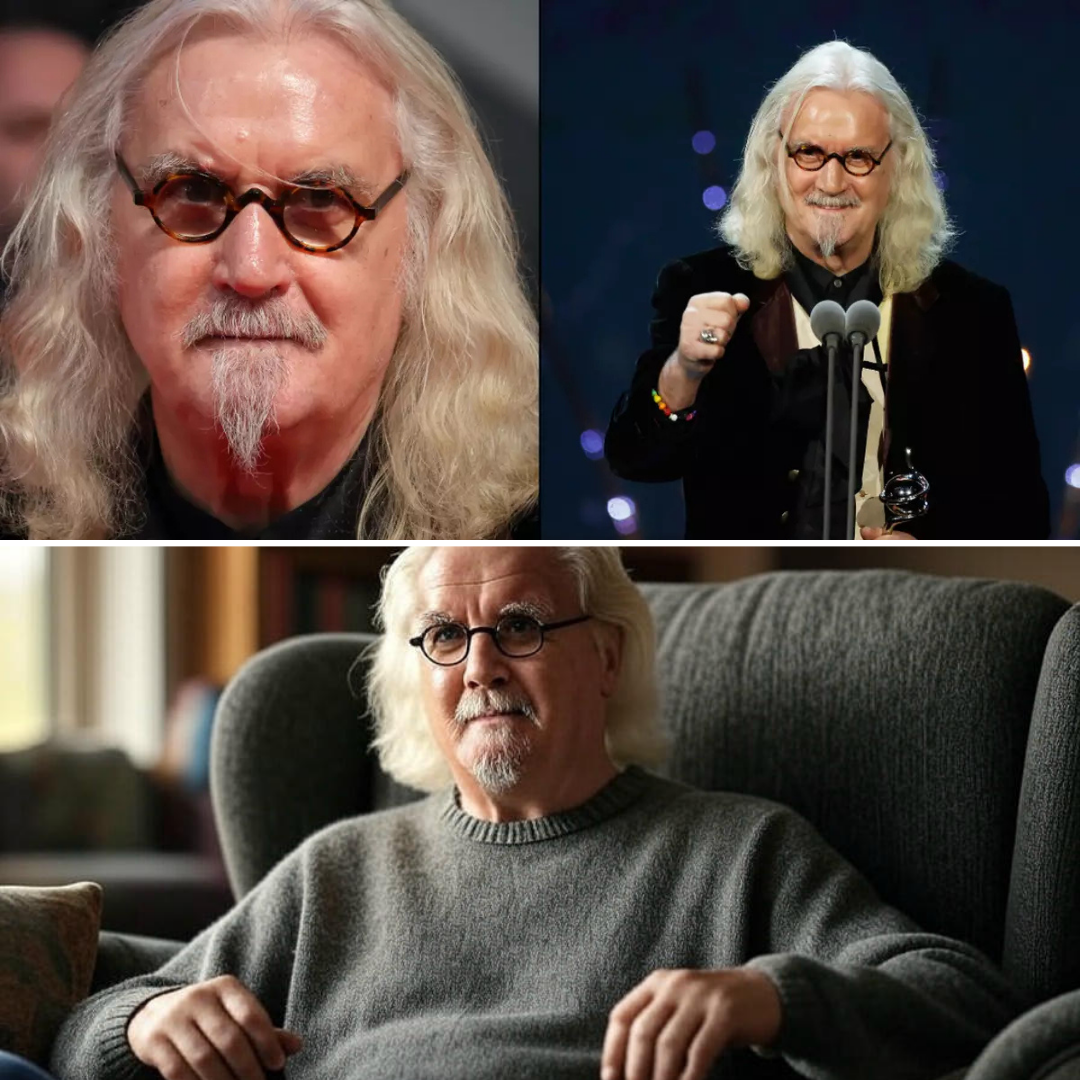

Sir Billy Connolly’s Courageous Journey: Facing Parkinson’s and Cancer with Humor and Heart

In a single day in 2013, Sir Billy Connolly, the beloved Scottish comedian known as “The Big Yin,” received life-altering news: he was diagnosed with both Parkinson’s disease and prostate cancer. The double blow, delivered hours apart, would have shattered many, but Connolly, with his trademark wit, faced it with resilience and a reflective quip: “The only thing I regret in my life is not being kinder to myself.” This moment, emblematic of his unyielding spirit, has inspired countless fans and reshaped his outlook on life, love, and laughter. Now, at 82, living in the Florida Keys, Connolly’s story of battling illness while embracing joy continues to captivate the world.

A Day of Reckoning

It was a surreal week in September 2013 when Connolly, then 71, faced a cascade of health revelations. As he recounted in The Guardian, the diagnoses came during a routine medical check-up in New York, where he lived with his wife, Pamela Stephenson, a psychologist and writer. The morning began with a call from his oncologist confirming prostate cancer, a shock softened by the doctor’s assurance: “First of all, you’re not gonna die.” Hours later, a second call revealed Parkinson’s disease, identified after a chance encounter with a Tasmanian surgeon in an Australian hotel lobby who noticed Connolly’s gait suggested early symptoms. “I went through to the bedroom to answer the phone,” Connolly told Radio Times. “Pamela was behind me—I thought she was gonna catch me. And she held me, and I went, ‘Oh Jesus’.”

The dual diagnoses were a stark reminder of life’s unpredictability. Prostate cancer, treatable in its early stages, offered hope, and Connolly later received the all-clear after successful treatment. Parkinson’s, however, is an incurable neurodegenerative disorder, causing tremors, balance issues, and memory challenges. Yet, Connolly’s response was quintessentially him: he blew a raspberry at the news, refusing to let it define him. “It just happened,” he said. “Deep despair and laughing are closely related, and I wasn’t in any pain.”

The Only Regret

In reflecting on his life, Connolly’s regret is not about missed opportunities or career choices but something deeply personal. “The only thing I regret in my life is not being kinder to myself,” he shared in a 2024 interview promoting his book The Accidental Artist. This introspection reveals a man who, despite his larger-than-life persona, has grappled with self-criticism, shaped by a challenging childhood in Glasgow marked by abuse and poverty. Therapy, encouraged by Pamela after his father’s death in 1989, helped him confront these demons, leading to sobriety and a newfound appreciation for self-compassion.

Connolly’s regret resonates universally, reminding us to balance kindness toward others with care for ourselves. His candor about mental health, rare for a man of his generation, has endeared him further to fans, who see him as both a comedic genius and a relatable human navigating life’s complexities.

A Life of Laughter

Born in 1942 in Glasgow’s Anderston district, Connolly’s journey from shipyard welder to global comedy icon is legendary. His early career as a folk singer in the Humblebums gave way to stand-up comedy, where his irreverent, improvisational style—often laced with profanity—earned him acclaim. His 1975 appearance on Parkinson catapulted him to fame, leading to a 60-year career that included 15 appearances on the show, roles in films like Mrs. Brown and The Hobbit, and winning I’m a Celebrity…Get Me Out of Here! in 2009. Knighted in 2017 for services to entertainment, Connolly’s influence is undeniable, with peers like Sir Paul McCartney and Whoopi Goldberg lauding his “anarchic genius.”

His humor, rooted in Glasgow’s working-class culture, never shied away from the absurd or the taboo. Even after his diagnoses, he incorporated his Parkinson’s tremors into his act, joking about his shaking hand. “I’ve always been easily made to laugh,” he told BBC Radio 4. “I’m a lucky man with my sense of humour. I can laugh myself out of most things.”

Living with Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s has undeniably changed Connolly’s life. By 2023, at age 80, he relied on a walking stick, used a wheelchair at airports, and needed Pamela to dress him each morning—a humbling shift for a man known for his boundless energy. Memory lapses, like forgetting his dog’s name while calling it in the street, brought moments of embarrassment, yet he faced them with humor: “You have to say, ‘Hey doggy doggy,’ which is terrible. I felt embarrassed for the dog.”

Despite these challenges, Connolly adapted. He stopped taking Parkinson’s medication early on, finding the side effects worse than the symptoms, though he resumed it as needed. He learned to “hypnotize” his shaking hand, glaring at it to quell tremors, a technique he likened to confronting hecklers during his comedy days. Drawing, a passion he discovered in a Montreal hotel room, became a creative outlet, though tremors sometimes interfered. “I draw with shakes in it, and it works,” he said, showcasing his ability to turn limitations into art. His book The Accidental Artist, released in 2024, features these drawings, blending humor and vulnerability to illustrate his life’s highs and lows.

Retiring from stand-up in 2018, Connolly mourned the loss of live performance but never ruled out a return. “I’ll never give up live performance,” he told BBC Radio 4 in 2023, hinting he might be persuaded for a one-off show. Now living in Florida’s warmer climate, advised by doctors to ease his symptoms, he spends his days fishing and drawing, declaring, “I’m not yet dead or broken.”

Confronting Mortality

The Parkinson’s diagnosis, coupled with his cancer scare, prompted Connolly to explore mortality in his 2014 ITV documentary Billy Connolly’s Big Send Off. Visiting funeral directors in Texas, a pet cemetery in San Francisco, and a Glasgow cemetery, he tackled death’s taboos with curiosity and wit. “I don’t think I want a resting place,” he said. “I want to be scattered on the wind.” His gravestone plans reflect his humor: after Pamela vetoed “Jesus Christ, is that the time already?” they settled on “You’re standing on my balls!” in tiny writing.

Connolly’s views on death have evolved. Once preoccupied with divine judgment, he now sees it as “a sudden nothing,” a mystery he no longer fears. “I used to think, ‘How will I be held responsible for my life?’ I don’t believe that anymore,” he wrote in Rambling Man: My Life on the Road. This shift reflects his embrace of life’s impermanence, finding joy in the present rather than dwelling on the inevitable.

The Role of Family and Friendship

Pamela Stephenson, Connolly’s wife since 1989, has been his rock. Their move to Florida, where they raise their three daughters, has been “fantastic” for Pamela, who supports Connolly through his daily challenges. “My wife puts my clothes on in the morning. It’s not very manly,” he admitted, yet her care has deepened their bond. His five children—two from his first marriage and three with Pamela—are among his proudest achievements, their laughter a constant source of joy.

Connolly’s friendship with the late Sir Michael Parkinson, who died in 2023, was another cornerstone. Their bond, forged during Connolly’s 1975 Parkinson appearance, weathered a brief rift in 2018 when Parkinson commented on Connolly’s slowed demeanor, upsetting Pamela. They reconciled, with Parkinson reflecting, “I would never deliberately hurt Billy.” Their shared memories, including evenings with Robin Williams in Scotland, were filled with “sick with laughter” moments, a testament to Connolly’s ability to forge deep connections.

A Lucky Bugger

Connolly’s resilience stems from his perspective as a survivor. A former welder in Glasgow’s shipyards, he escaped the era’s hazards—like asbestos exposure—that claimed many colleagues. “I probably shouldn’t have escaped, but I did,” he wrote in The Accidental Artist. “Maybe what doesn’t kill you f**ks you up for life, but at least I’m still here.” His survival, from a traumatic childhood to health battles, fuels his gratitude. “I’m a lucky bugger,” he declared, a sentiment echoed in his refusal to be defined by illness.

His humor remains a lifeline. Even as Parkinson’s limits his mobility, he finds absurdity in the mundane, like shouting “doggy doggy” or joking about his gravestone. This ability to laugh, coupled with therapy’s transformative impact, has made him a beacon for others facing chronic illness. “Therapy saved my life,” he said. “I don’t have any regrets. I’m perfectly happy.”

Inspiring a Global Audience

Connolly’s story has resonated widely, amplified by social media and his candid interviews. In 2024, his BBC One series In My Own Words offered an unflinching look at his triumphs and struggles, drawing praise for its honesty. Fans on platforms like X have shared how his humor and humility inspire them, with posts noting, “Billy Connolly’s ability to laugh through Parkinson’s is a masterclass in living.” His advocacy, albeit unintentional, has raised awareness about Parkinson’s, with organizations like Parkinson’s Europe citing his openness as a catalyst for dialogue.

A Legacy of Joy

Sir Billy Connolly’s dual diagnoses in 2013 tested his spirit, but they also revealed his core: a man who finds light in darkness, who regrets only not being kinder to himself, and who lives each day with humor and heart. From Glasgow’s shipyards to Florida’s shores, his journey is a testament to resilience, the power of laughter, and the importance of self-compassion. As he fishes and draws, surrounded by family, Connolly remains a global treasure, reminding us to confront life’s challenges with a raspberry and a smile.