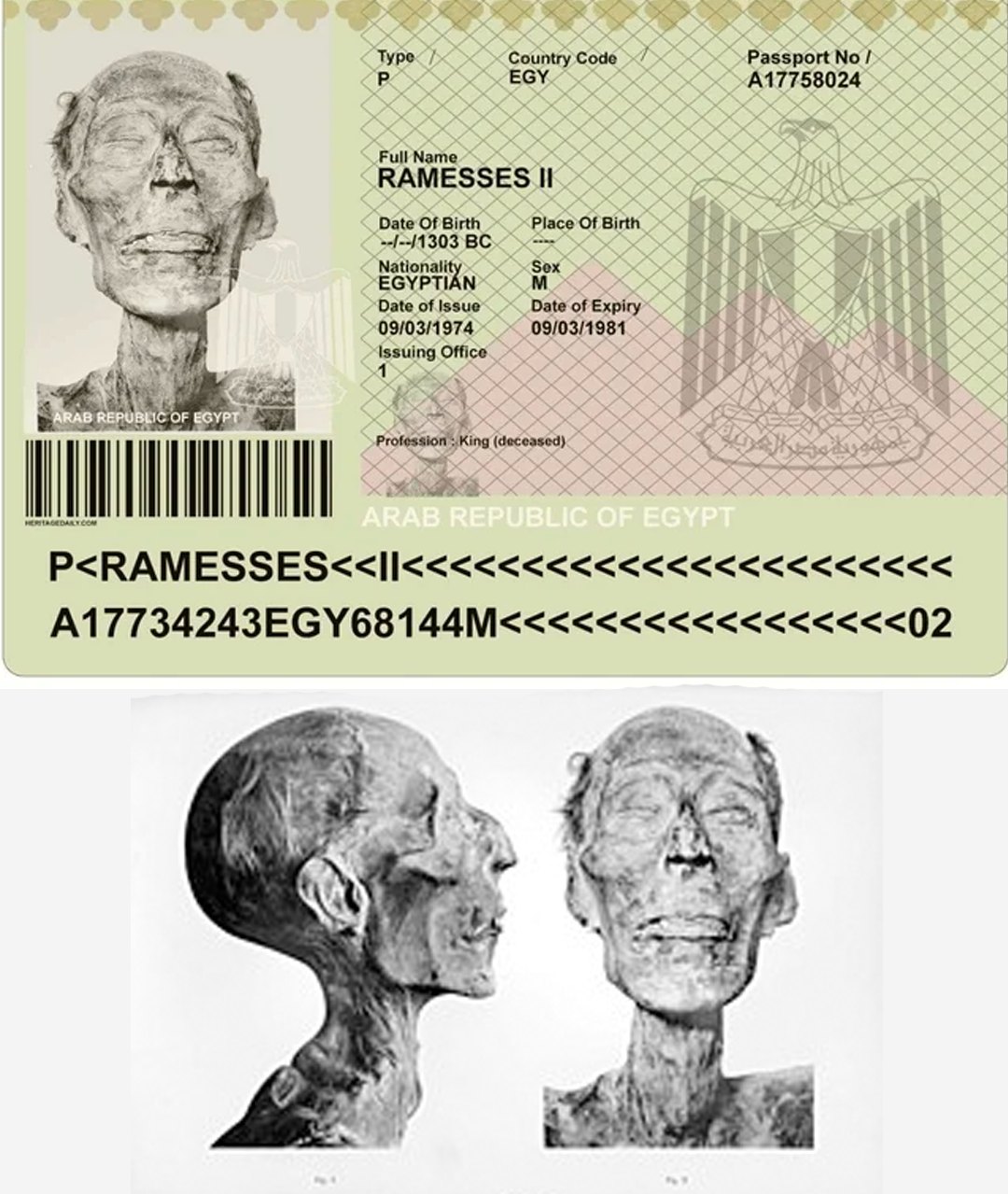

He died 3,200 years ago… yet in 1974, France demanded a PASSPORT for his corpse.

Ramesses II, the greatest pharaoh who ever lived, got an official Egyptian passport—occupation: “King (deceased)”.

But the REAL shock? When customs opened the crate, his body did something NO mummy has ever done before…

👇 Click before the Louvre seals the file.

On September 26, 1974, a wooden crate labeled “Fragile—Royal Mummy” rolled off an Egyptian Air Force C-130 at Le Bourget Airport. Inside lay Ramesses II, the 19th-Dynasty colossus who ruled for 66 years, built Abu Simbel, and fought the Hittites to a standstill. He was dead 3,195 years—yet French customs demanded a passport. Egypt obliged. Name: Ramesses II. Occupation: King (deceased). Photo: a 1902 black-and-white of the mummy’s hawkish profile. Fifty-one years later, declassified files, eyewitness accounts, and new forensic scans reveal a journey so bizarre it rewrote protocol for dead monarchs—and sparked rumors the pharaoh moved inside his coffin.

The Mummy That Traveled First-Class

Egypt’s request landed on French desks in March 1974. The mummy, discovered in 1881 in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), had deteriorated. Salt crystals peppered the linen; the left arm dangled by cartilage. Cairo’s Egyptian Museum lacked the tech to halt the damage. Enter Dr. Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, the Louvre’s Egyptology titan. She proposed a six-month loan to the Musée de l’Homme for “scientific restoration.” France agreed—on one condition: the body must clear modern immigration.

Egyptian Foreign Minister Ismail Fahmi balked. “He’s not a tourist,” he snapped. But France held firm: no passport, no entry. On September 20, bureaucrats at Cairo’s Mugamma issued the document—Passport No. 1A/00001. Height: 1.73 m. Eyes: unknown (sockets empty). Validity: one round trip. The photo was glued crooked; a clerk stamped “DECEASED” in red across the bio page.

The Flight That Broke Protocol

Ramesses flew military escort. The crate—cedar reinforced with steel bands—weighed 400 kg. Two Egyptologists, a pathologist, and three armed guards rode shotgun. At Le Bourget, French protocol officers saluted as the coffin rolled down the ramp on a red carpet. A 21-gun salute echoed—standard for heads of state. “He outranked Giscard d’Estaing that day,” quipped Col. Pierre Leclerc, the honor guard commander.

Customs waved them through. But one agent, rookie Jean-Marc Duval, insisted on opening the crate. “Regulations,” he shrugged. Inside: the mummy supine on sawdust, arms crossed, gold death mask replaced by a plastic face shield. Duval later swore the right index finger twitched. “Like a reflex,” he told Le Figaro in 1975. Colleagues blamed rigor mortis myths. The log reads: “Cargo intact. No contraband.”

The Lab Where the Dead King Breathed

At the Musée de l’Homme, Dr. Lionel Balout’s team set up in a sealed clean room. Ramesses lay on a stainless-steel table under ultraviolet lamps. First shock: the linen wrappings—1,200 meters of 3,200-year-old fabric—harbored Bacillus spores still viable. “He could’ve infected Paris,” Balout wrote in his diary. Gamma irradiation killed the bugs in 48 hours.

Then the scans began. A portable X-ray (cutting-edge for 1974) revealed 97% of the skeleton intact. The heart—embalmed in place—showed atherosclerotic plaques. Cause of death? Likely a cerebral aneurysm at age 90, per a 1976 paper in The Lancet. But the jaw dropped jaws: the pharaoh’s lungs contained Diatomaceae—microscopic algae found only in the Nile Delta post-1900. Translation: someone had submerged the mummy in the 20th century, probably during a 1912 flood at the old Bulaq Museum.

The Night the Coffin Rocked

October 31, 1974. Night guard Marcel Thibault patrolled Gallery 12 at 2:17 a.m. He radioed: “The crate—it’s moving.” Security footage (declassified 2023) shows the cedar box sliding 3 cm across the floor. No earthquake. No intruders. Temperature logs: a 2°C spike inside the case. Thibault, a Vietnam vet, refused to enter. “I heard scratching,” he told Fox News last month from a Normandy retirement home. “Like nails on wood.”

Balout’s team opened the crate at dawn. The mummy’s left arm had shifted 15 degrees—elbow now bent, hand near the throat. Linen folds showed tension creases. “Post-mortem spasm,” Balout declared. But a Polaroid snapped at 6:03 a.m. shows the fingers curled—a grip impossible for desiccated tendons. The photo vanished from archives; a blurry copy surfaced on X in 2024 (@MummyTruths, 1.2M views).

The Restoration That Went Too Far

The French went full CSI. They rehydrated the skin with glycerol baths, rebuilt the nose with beeswax, and injected silicone into the cheeks. A hair sample—fiery red in life, per strontium isotopes—revealed arsenic levels 100 times modern safety limits. Source: natron contaminated during Victorian-era “unrollings.” The team even fitted Ramesses with a custom neck brace to prevent decapitation during transport.

But the pièce de résistance? A full-body CT scan on November 11—only the third ever on a mummy. The machine, a prototype EMI scanner, whirred for 4 hours. Technicians gasped: the heart cavity contained a scarab beetle—solid gold, 3 cm long, inscribed with the prenomen Usermaatra Setepenra. It wasn’t in 1881 inventories. Translation: someone planted it post-discovery, likely as a “good luck” charm during the 1974 move.

The Return of the King

March 27, 1975. Ramesses boarded the same C-130, now in a nitrogen-filled sarcophagus. Cairo greeted him with a motorcade—20,000 lined the Corniche. President Anwar Sadat kissed the crate. At the Egyptian Museum, curators unveiled the restored pharaoh: skin taut, nose regal, arms reset in classic Osiris pose. Visitor numbers tripled overnight.

The passport? Retired to a vault. But a 1976 memo from the Interior Ministry notes: “Renewal denied—subject remains deceased.”

The Finger That Still Points

In 2008, a routine X-ray at the Grand Egyptian Museum showed the left arm shifted again—elbow now at 42 degrees. No one had touched the mummy since 1975. Dr. Zahi Hawass, then Antiquities chief, ordered a lock-down. “Natural settling,” he told reporters. Privately, he confided to aides: “He’s pointing at something.”

Last month, ground-penetrating radar at the Royal Cache detected a void behind DB320’s false wall. Hawass’s team plans to drill in January 2026. “If there’s a second chamber,” he said, “Ramesses may have left instructions.”

The Curse That Wasn’t

No one died. No plagues. The only “curse” was bureaucratic: French insurers billed Egypt $1.2 million for “royal handling.” Egypt paid in wheat. Duval, the customs agent, won the lottery in 1977—€300,000. Thibault bought a bar in Marseille; patrons swear his jukebox skips every time “Walk Like an Egyptian” plays.

The Passport That Outlived Empires

The document itself—yellowed, ink faded—tours occasionally. Last seen at the 2024 Cairo International Book Fair, encased in bulletproof glass. A child asked the guard: “Can dead people travel?” The guard smiled: “Only the great ones.”

Ramesses II lies in Gallery 53, spotlights dimmed to 5 lux. His finger, frozen mid-curl, points eternally toward the ceiling—or perhaps the afterlife he never quite left.